Microsoft PowerPoint 2013 Tutorial

Templates/Themes | Tutorial Main Menu | Training Homepage

Section 8: Creating an Effective Presentation

Microsoft PowerPoint 2013 has many of the elements necessary for a successful presentation, but even with all of its many features, it does not guarantee an effective (or even an informative) presentation. In this section, then, we will cover some guidelines on making a successful and informative presentation.

Accessibility

One of the most important things to keep in mind when preparing the slideshow for your presentation is accessibility. If some in your audience are unable to see your slideshow as well as others, then your presentation will not be as effective.

Text Size. In creating your slideshow, your text should be no smaller than 24 point font. To be safe, most of the text of your slideshow should have 30 point font.

Text Font. The font you use should be easy to read, as well as simple. Avoid using fancy or calligraphic fonts in your slideshow.

Text Color. Use a text color (as well as your background color) that will make your slideshow as readable as possible. If you are accustomed to presenting in a dimly-lit or dark room, then a dark background with light text might be a good idea. If you are going to be giving a presentation in a room with a lot of light, it would be beneficial to use a dark text against a light background. [1]

Slide Layouts. Rather than creating your own text boxes, use the slide layouts already provided by PowerPoint. [2]

Alternate Text. If you have a version of PowerPoint which supports alternate text for images, be sure to add it for the benefit of those who use screen readers.

Handouts. Using handouts (see Section 6) is an excellent way to make sure that everyone will be able to follow along during your slideshow.

The Proper Use of Graphics

The proper use of visual aids, such as graphics, can be quite helpful. They can serve a medium through which a particular point may be better expressed. There are times, however, when visual aids can become a distraction. In that case the use of graphics can hurt rather than help your presentation.

Within the context of a presentation, then, graphics can be denominated into four distinct classes: 1) meaningless graphics, 2) tangentially meaningful graphics, 3) illustrative graphics, and 4) visually evident graphics [3]. We will briefly cover these four types of graphics, as well as how they can help or hurt your presentation overall.

1) Meaningless Graphics. This first type of graphic conveys no relevant information to your audience, and ends up doing nothing more than taking up space. Below are a couple examples of this first type of graphic.

Figure 8-1

Example 1. In our first example, the slide contains a quote, as well as an artistic representation of the person being quoted. Granted, the artist (Rembrandt) has certainly painted a magnificent portrait, but the image of his work does not actually add anything to the presentation itself. Instead, it merely serves as a distraction from the real purpose of the slide, which is to present a quote. In this case, it is the quote itself that is meant to be an aid to a particular point in your presentation, and therefore the image beside it diverts the attention of your audience to itself rather than on the substance of your presentation. In effect, the audience ends up paying more attention to Rembrandt than to what you have to say, which can hurt your presentation overall.

In some cases, an entire graphic can be classified as meaningless. In others, parts of a graphic may be meaningful, whereas the rest is not. Consider, for example, a screenshot (that is, a snapshot of what is currently on your computer screen).

Figure 8-2

Example 2. In our second example, a slide containing a screenshot, only a part of the graphic is meaningless. Although the open browser window is obviously being used for the purpose of demonstration, the rest of the screenshot contains several images which can be a distraction to the screenshot's actual content.

In this case, it is important to remember that when taking a screenshot using the Print Screen command, whatever is on the screen will be captured, without exception. This may include other open windows, as well as icons and widgets on the desktop. In this case, the audience's attention is drawn away from the intended focus of the screenshot, to the jellyfish desktop wallpaper, the image of the penguins, the calender, clock, and weather widgets, as well as the personal information in the sticky note. The audience may find these irrelevant aspects of the slide more engaging than the relevant aspects, and so it is important to crop the screenshot so as to include only those parts of the screenshot that are pertinent to the particular slide.

Tip. Whenever you would like to include a graphic in a particular slide of your presentation, you should always ask yourself the following questions: "For what purpose am I including this image?" and "In actuality, can the slide still present the information adequately without this graphic?" If you can honestly answer that the purpose for including the graphic is for purely aesthetic reasons, and the image does not provide or help to convey any relevant information, than it is probably wise to exclude the graphic altogether.

2) Tangentially Meaningful Graphics. Some graphics assist you in expressing a particular point or carry fully relevant information, whereas others have only a indirect or peripheral relation to the actual content of the slide. This second type of graphic is termed tangential, because graphics in this category only touch upon the primary subject matter, and contribute little to the substance of the presentation itself.

Figure 8-3

For instance, while the use of a logo or seal (such as that of a university) may be quite appropriate for the first and last slides of a presentation, using it repeatedly on every slide causes it to lose some of its import. The above slide can serve as an example of a proper use of a tangentially meaningful graphic, as it is the first of several slides dealing with NC State University.

3) Illustrative Graphics. This third type of graphic is called illustrative, because it has a direct relation to the contents of the slide, or it serves to assist you in expressing a particular point in your presentation.

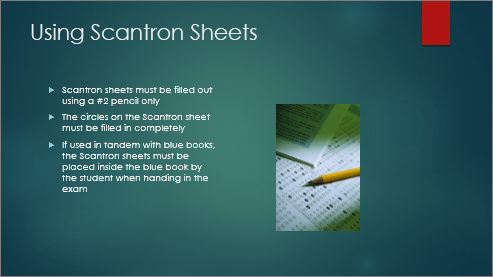

Figure 8-4

Take for example the above slide, which deals with the use of Scantron sheets in the context of an exam. The graphic of a Scantron sheet properly filled out, together with a #2 pencil, serves to illustrate the content of the slide on the left.

Tip. It is very common to confuse graphics used for the purposes of illustration, and those which are meaningless. It is important to remember that illustrative graphics have a direct relation to the content of the slide or presentation, whereas meaningless graphics simply take up space on the slide.

4) Visually Evident Graphics. This fourth and last type of graphic not only has a direct relation to the content of the slide or presentation, but also actually conveys information in itself, or serves as a signification within the overall context of the slide. These graphics are ideal for use in a presentation, precisely because it serves as an illustration of a particular point, or is visually descriptive of the material presented. For this reason it is this type of graphic which should be used most often in a presentation.

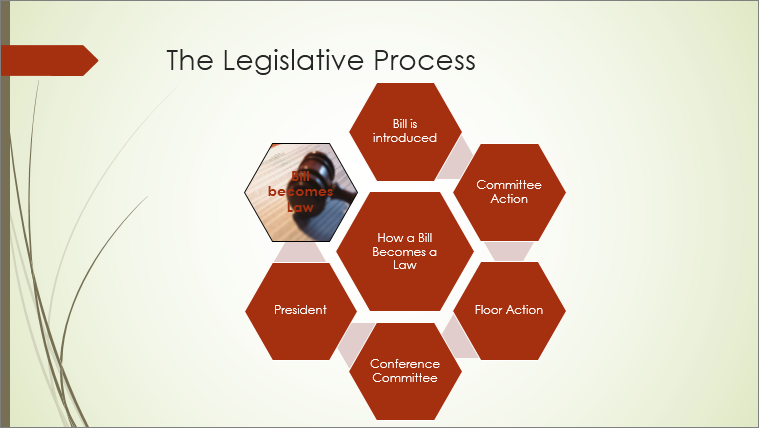

Figure 8-5

In the above example, the graphic used as the background for the final part of the flowchart visually describes the end result of the legislative process.

The Proper Use of Animation

Although in many circumstances animation can be useful for emphasizing a particular point during a presentation, frequent or improper use of animation can seriously divert the attention of your audience, in some cases even preventing you from reaching them at all. You can use the four categories used above for graphics to guide your decision process as to whether or not a particular animation is necessary. Be certain that any animation you include in your presentation is actually conducive to getting your point across, and not simply there for show.

Using the Right Amount of Text

How much text one should include in each slide depends on the circumstances in which you are giving your presentation. There are two approaches you could take, depending on the context in which you are speaking. The first approach would seem to be more appropriate in a business setting, such as a staff meeting or perhaps a conference, while the second might be more appropriate for an academic setting such as a lecture.

The Bullet Approach

In a business setting, the slideshow could be seen as a "map" of sorts, serving as a guide or outline for your presentation. In this approach, the amount of text in your presentation is governed by the "six by six" rule. That is, there should be no more than six words per bullet, and no more than six bullets per slide of your presentation [4]. Following to this rule, the inclusion of any additional text would be considered writing out your presentation, rather than using the slideshow as an aid to conveying salient points.

As an example of this approach, let us consider a thesis paper, comparing the presentation as a whole to the paper itself, and the slideshow to its outline. It would be outside the scope of an outline to write out all your arguments with the same detail as your paper. In the same way, you would not want to include your entire presentation in the slideshow, as this is not its purpose.

According to the "six by six" rule, therefore, having more than six words per bullet or six bullets per slide will make your slideshow too cluttered. This would distract your audience, and only diminish the overall effectiveness of your presentation.

The Sentence Approach

In an academic context on the other hand, using complete sentences rather than short six-word points in each slide has the advantage of conveying more information, thus enabling students to take more detailed notes. In addition to the presentation itself, printing handouts of the slideshow and giving them to students can serve as an aid to study.

Another circumstance in which this approach might help make your presentation more effective, is when you are giving a presentation in a language that is not your native tongue, or if your particular dialect is different enough from your audience that unaided speech might present a difficulty in understanding. Putting the text of your slides into complete sentences allows the audience to use the slideshow as a more complete reference, and aid their understanding during your presentation.

A constant temptation in this second approach, however, is to use the slideshow as a medium through which you write out all the material contained in your presentation. It will be necessary to be cautious when putting together your slideshow, making sure that you are not including so much detail that the slideshow becomes more of a crutch and less of an aid during your presentation. Relying too heavily on the slideshow has the effect of ruining a perfectly well-researched presentation. In trying to limit how much text you include in your slideshow, try to use complete sentences only in your main points, and avoid going into too much detail in your secondary points. It is rather the spoken part of your presentation that should be the most in-depth, providing your audience with the most detailed information.

Rehearsing Your Presentation

Although researching the content of your presentation and putting together a professional grade slideshow are both important, they are only parts of an effective presentation. It is important that you rehearse your presentation, paying attention to your posture, emphasis, volume, gestures, and timing. It is this rehearsal of your presentation that can make all the difference in making it an effective one.

You have now reached the end of the tutorial for Microsoft PowerPoint 2013. To return to the tutorial's table of contents, click Tutorial Main Menu. To select among different training options, click Training Homepage.

[1] "Microsoft PowerPoint," IT Accessibility, OIT NC State: https://oit.ncsu.edu/itaccess/microsoft-powerpoint.

[2] "How to Make Presentations Accessible to All," Web Accessibility Initiative: https://www.w3.org/WAI/training/accessible.

[3] Guidelines provided by professor John F. Raffensperger from the College of Management at the University of Canterbury.

[4] Guidelines provided by the College of Eduction at the University of Wyoming.